|

| From VMI Cadet to Key Staff Officer of the AEF |

In 1957, 39 years after the 1918 battles in France, George Marshall was interviewed by his official biographer Forrest Pogue. In the past, I've drawn on the recordings of these revealing interviews to gain insights on events like the Meuse-Argonne Offensive or personalities such as General Pershing or Premier Clemenceau, with which Marshall had direct experience. In this article, the focus is on Marshall, himself. I've combed the manuscripts of the interviews for places where the general—an austere, highly reticent individual—revealed interesting aspects of his personality and unique experiences in the Great War. These are excerpts from those interviews in which the questions and spontaneous comments from the general jumped around chronologically. I've tried to rearrange them at least semi-chronologically. MH

1. Going Over There

I left San Francisco [in May 1917] . . . and went directly to Governors Island. The next thing of excitement that occurred was that General Pershing arrived, headed for Europe. I found out that he had asked for my services. He didn't do it personally, but his chief of staff did-his new chief of staff, General Harbord. But when General Pershing found that I was with General Bell, he had them drop the request and, therefore, I didn't go, though I didn't know of it at that time. . . General Pershing arrived in civilian clothes and straw hat. We put him on the ferryboat at Governors Island at a secluded dock and sent him over to the Baltic which he boarded for his trip to Europe [28 May 1917].

Then I received a telegram that my services were requested by General Sibert, the man who had built the Gatun Dam [at Panama Canal]. . . He had asked for me to go and I was to report to him. He made my desk, my services, the headquarters for troops just coming in to go to Europe in the first convoy, which was to be the First Division. [Subsequently] we got on board the Tenadores [4 June 1917], and I was in the same stateroom with [future WWII General] Lesley McNair.

[During the voyage] something occurred there that I never forgot, because it was about as significant an indication of our complete state of unpreparedness as I have ever seen. I was standing up under the bridge and they had mounted a three-inch gun on a pedestal mount on the forward part of the deck, and these trim-looking naval files under a naval noncom were rigging up the gun. Having dealt with this multitude of recruits in this regiment as we had and their complete ignorance of their weapons or anything, I thought to myself, "Well, thank goodness, there is one thing that's organized, the Navy." Just then the captain called down to this yeoman, or whatever he was, in charge of this detail and said to him in a very strong voice, he said, "Have you your ammunition?" And this fellow in a rather offended voice replied, "No, sir, we haven't any ammunition." Well, I thought, "My God, even the naval part isn't organized here and we are starting off to Europe." It was altogether a terrible exhibition of our paucity of means with which to go to war.

2. Called to the Front [1918]

[While Marshal was at a school in Langres] the great German offensive broke loose March 21st and was going on at the time I lectured. The first day, the 21st, of course we just got the news of the affair and a little bit of the extent of the affair. You will recall the British Fifth Army was literally destroyed in this first part of this offensive and a great gap was made in the line. . . The second day the thing was getting very much hotter, we could tell that. The German advances were far greater than had been customary in trench warfare. They generally made very, very short advances. . .

[On 29 March] we were having breakfast when an order came in for me to return to the First Division immediately and a car would meet me north of Chaumont near Domremy. About a half an hour later, or less than that, because I got out as fast as I could, I left for the First Division. I got up there and found it was just preparing to leave for the scene of the battle where the British Fifth Army had been driven out and very badly handled. . . We moved immediately, going south of Paris motoring. The troop trains were going south of Paris, too, and the motor trains and all were going south of Paris, because there was too much confusion north of Paris in supplying the French Army and everything to meet this great German offensive.

Then the next morning we started again up the trail. We were now west of Paris and we finally came into these assembly areas as they called them. I learned a great deal about troop movements during this procedure, because it was a tremendous affair and I thought perfectly, beautifully done by the French in their handling of the railroads. The trains would come through, it seemed to me, at ten minute intervals, and I would have to be at the train when it came in because I didn't know who was on it-maybe part of a French division or part of an American division. If it was an American division, I had to catch the fellow and give him his orders as to where he was to march to after he detrained. So we had a very hectic time there grabbing these trains as they came in.

3. Early Experience of Combat

We learned a great deal about fighting up at this time. It was a continuous affair, terrifically heavy artillery bombardment. The night was just hideous. I used to try to sleep upstairs in this chateau, but they drove me down when they began hitting the building with these 8-inch shells which sounded like the end of the world. So I found more composed rest down in this deep wine cellar that I have already referred to. Then we had a very difficult situation. We had the first mustard gas attack and that was a vicious thing. The brigade commander had directed the regimental commander at this town-he sent word up to him-to evacuate the town and go out into the fields and woods. Well, it was raining hard and shells were breaking all over the place. So the fellow preferred his dugout. Of course, the worst thing you can do with mustard gas is get in a wet dugout. That just permeates the whole business. They were ordering him out and he wasn't going. So I was sent up. The brigade commander didn't go. I was sent up from division headquarters with orders to relieve him, and that isn't very pleasant.

4. The Performance of the AEF at St. Mihiel

It went off pretty well; it went off very well, as a matter of fact. I think we could have gone a little farther at the end if the corps commanders had followed out their orders. The order provided that when they got to the line rigidly specified, specifically outlined, and there was any opportunity to go forward, they should send forward battalions with some artillery and reconnaissance units and push ahead as fast as they could. They didn't do this. In one division this was proposed and that was done by Douglas MacArthur, who was chief of staff of the Forty-second Division. He wanted to push right on at that time. The trouble was none of the others had gathered themselves, and General Drum and the army commander thought we should leave well enough alone. Undoubtedly, if they had pushed on, they would have gone much closer to Metz at the first lunge. However, they already had authority to organize a battalion or regiment in the division and push ahead with that, but they didn't do that. Of course, it was their first big battle and there's always much confusion and there's always much uncertainty as to what the exact conditions were which is to be carefully considered when you are trying to judge whether you did this just right or not. You didn't have a Stonewall Jackson who had been experienced in many fights already.

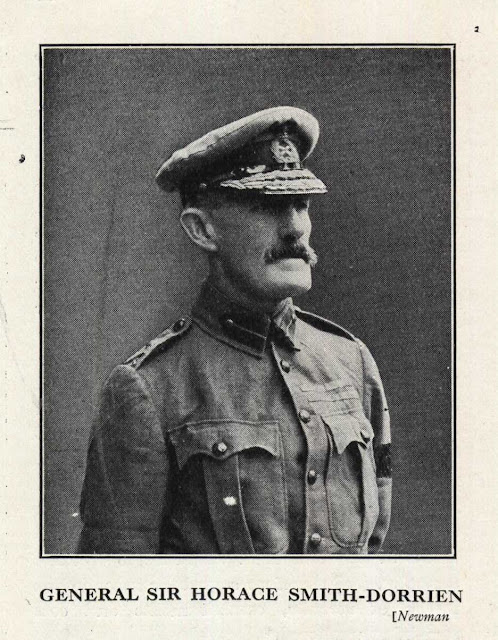

|

| Lt. Marshall, 1907 Instructor, School of the Line, Ft. Leavenworth |

5. The Move from St. Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne

[After St. Mihiel] the complications now began. I had been concerned now with the full battle. Now suddenly I was called over to headquarters, which was across the street, and they outlined the Meuse-Argonne, That's the first time I'd ever heard of it, and that's what the other fellows on the staff had been working on-the plan for the deployment for the Meuse-Argonne and the initial plan for the battle. I was told to concentrate the troops and I was given the line-up they were to have in the battle. That was my first intimation of the Meuse-Argonne battIe.

Finally came the great concentration for the Meuse-Argonne. It went across the rear zone of the St. Mihiel battle and then cut up towards the Meuse-Argonne front. When I went to work on this troop movement, it was one of the most difficult ones I have ever heard of in military performance prior to the great rush across Europe in the last war. I found that I was familiar with the names of practically every village and every city, more so almost than the little villages near my home, because they were all on this Griepenkerl [a German tactical guide adopted by the U.S. Army] map and had all been involved in Griepenkerl problems and were right in the track of these great moves we were making towards the Meuse-Argonne front. It seemed rather a commentary on the fact that we were being criticized, even in Congress, for using German maps, and all when it developed afterwards they were most useful to us in our being familiarized with the very ground we were going to fight over.

6. Problems in the Meuse-Argonne

Once we got into the battle, the great problem was to resume the advance. The division on the left, the division next to the Meuse-Argonne forest, got into trouble and the First Division had to be hurried out of support position and carried up to the front. They had to travel more or less off the road over these deep trenches and, with the machine gun carts and all, it was a very difficult thing to do. No Man's Land was some kilometers in width and it was a morass that didn't look like there was a space ten yards square that hadn't been struck by a great shell. It was a morass. There was no trace of the roads left at all except the Route National, and there was some trace there, but in the retirement from a German attack, the Italians had blown up the road so successfully that we had a terrible time getting around the crater.

So it was the crossing of No Man's Land and getting the artillery across that was so very difficult and so very important. One commander, who had previously lost his regiment for something a long time back and now had it again-he didn't have the light [artillery] regiment this time-he had a ISS-mm regiment and these heavy guns. And he hastened up on his own initiative, crossed No Man's Land, and the weight of these guns completely wiped out this very poorly ballasted trail that we had made across No Man's Land and set the affair back about a day and a half, which was a great tragedy at the time, as we were trying to get light artillery across and supporting troops across.

As a matter of truth, the men advanced very well at the start. Then they got into these dugouts and they got after souvenirs. They went into the dugout for a German in a sense and then they stayed for a souvenir and the whole advance lost its momentum, and the Germans very quickly readjusted themselves and put up a vicious defense from there on. As a matter of fact, if the troops could have been kept together and have gone straight ahead, they probably could have gone as far that first day as we made in the first month, because we fought a very desperate battle with the Germans after that halt or loss of momentum.

7. The Final Push in the Meuse-Argonne

We finally came up against what you might call the northern line and there we got ready for the great attack which led up to Sedan. I've forgotten how many divisions took off in that, but we tried to get them rested a little bit. In order to do that, we had to hold the other divisions in line when they were just tired to death. But there was no other way to manage it. It was very necessary to go and see the division commanders and see the regimental commanders. In some of them, the regiments had lost all organization and were just groups of men, but they had to hold on and they fought on so that these partially rested divisions could go forward in the final attack on November 1st, I think it was, which led up finally to the heights above Sedan.

I would go up to the battle front and it was very hard to get up there on account of the traffic. After you got across No Man's Land, the only way you could do it was to get on a horse and go up there that way. I did that and I did that with General Drum, who was chief of staff of the [First] Army, and, of course, we had a great deal of our debating while we were riding. . .

The great trouble here was keeping the various organizations along the front really aware of what was happening along other portions of the front, because each one thought he was the only one who was having this desperate situation, when, as a matter of fact, everyone was having it pretty much and we were now getting into some French troops over towards Verdun where we had both Americans and French. The Germans had hard luck on this front. They had had several Austrian divisions on that front. They were a little bit leery about them and, as you recall, the Austrians surrendered first. So they kept some Germans there to stiffen up the Austrian front which was to the east and northeast of Verdun. Nothing happened on that front at all, so they withdrew the German divisions that were stiffening up the Austrians and the next day we attacked on that front and the Austrians pretty largely folded up and let us make a considerable advance.

|

| A Postwar Assignment as Pershing's Aide Kept Marshall on the Road to High Command |

8. About His Superiors

General Pershing as a leader always dominated any gathering where he was. He was a tremendous driver, if necessary; a very kindly, likeable man on off-duty status, but very stern on a duty basis.

I wasn't on intimate terms at all with Marshal Foch, though I travelled with him quite a bit in this country and saw him quite often with General Pershing. He was rather resentful if I said anything when I was with General Pershing. Nobody below the grade of a full general would say anything in front of Foch in the French army, and I was talking up there with a very much lower rank to General Pershing when he was in conversation with Marshal Foch.

I know when I received the Croix de Guerre in the plaza at Metz [30 April 1919]. . . the French general that was tried afterwards and imprisoned? I was very fond of him, came to know him very, very well. (Petain?) Yeah, Petain.

I saw General Charles Summerall, who was really the iron man. He was the nearest approach to the [Stonewall] Jackson type that I saw in the war. He was a wonder to watch when the fighting was on as a leader. His influence on the men was tremendous.

I thought [Chief of Staff] Peyton March was a great administrator and a very arbitrary, tactless man. I think his greatest error was having around him a number of men that copied his type. He needed exactly the opposite type as his principal functionaries, it seemed to me.

I would say this in regard to all this being written about my being hostile to General MacArthur. In the first place, it is damn nonsense. . . I don't think I ever said an adverse word about General MacArthur in front of the staff, though he was very difficult-very, very difficult at times-particularly when he was on a political procedure basis. I don't ever recall saying a word in front of the staff, and I do recall suppressing them. I wrote his citation for the Medal of Honor to see that he got it.

9. In the 1939–41 period, did you have the feeling that you were seeing 1915–1916 all over again?

In 1939-1941 I saw very much reflections of the things of '15-'16 all over again. In fact, in some ways, very little occurred that didn't seem to me was a repetition, but what disturbed me most of all was to find the army, the War Department, and the country in the same shape again. In the same shape again! I was getting rather hardened to coming in when everything had gone to pot and there was nothing you could get your hands on, and darned if I didn't find the same thing when I came into the Korean War. There wasn't anything. We had a terrible time getting ourselves together.

10. Lessons for Future Wars?

. . . Why, it was a continuous series of lessons. Most of them, what to do and quite a number what not to do. I learnt the technique of high command, the technique of logistics, the technique of a great many of those things, and I saw troops under various conditions. I saw their regard for them in many ways that were an education to me, and I saw so many of the things they did wouldn't have worked with American troops at all. That was all very, very helpful and I would find myself leaning on that knowledge in dealing with things in World War II.

The big thing I learnt in World War II was the urgent necessity of frequent visits. Well, as I used a plane all the time and about every other week, I would go on the road before we got into the general war. I would visit most of the places in the United States with fair frequency. I know when I went out to Fort Sill the first time, I found out it was the first time the chief of staff had ever been there in the history of the place. I was there time after time, but I could move quickly and I could act quickly. I was abreast of what was going on all over the place. I could sense their reactions and I could see how they felt urgently about this or that, which we at headquarters did not really feel so much, but I would come to an understanding in those ways and I could correct things almost instantly, particularly after Congress-without my request-placed first $25 million and then $100 million at my disposal with no accounting required.

Source: Transcripts of the entire collection of 10 tapes covering Marshall's entire career can be found starting HERE.